Putting AI to work in the healthcare industry is a tricky business; it’s even more so in oncology, where the stakes are especially high. Biotech startup Valar Labs is aiming high but starting small with a tool that accurately predicts certain treatment outcomes, potentially saving precious time for patients. It has raised $22 million to expand to new cancers and therapies.

Every cancer is different, but many have established best practices honed over years of testing. Sometimes, however, that means going through months of a given treatment regimen in order to find out whether it works.

Bladder cancer is one of these, Valar’s co-founders explained to TechCrunch. A common first treatment recommended by oncologists, called BCG therapy, has about a coin-flip’s chance of working — which is actually pretty good! But wouldn’t it be nice to not have to flip that coin to begin with? That’s the problem Valar is trying to solve.

CEO Anirudh Joshi said that the team met one another at Stanford, where they were looking into AI support for clinical decision-making. In other words, helping both patients and doctors decide which treatment path to take, whether it’s out of two or a dozen.

“What we learned is that the majority of cancer patients today, their treatment plan is really unclear,” Joshi said. “They have options, but it’s hard to say what will do well — you just have to try stuff. So our whole idea was to make this an informed decision. In bladder cancer treatment, only one in two patients responds to standard care. If we knew which patient was which, we wouldn’t have to waste a year of therapy on something that doesn’t work.”

The first test they’ve developed, called Vesta, is focused on this specific situation. And it isn’t some theoretical software solution: The team worked with a dozen medical centers around the world to study over 1,000 patients and learn what exactly makes them respond to certain therapies.

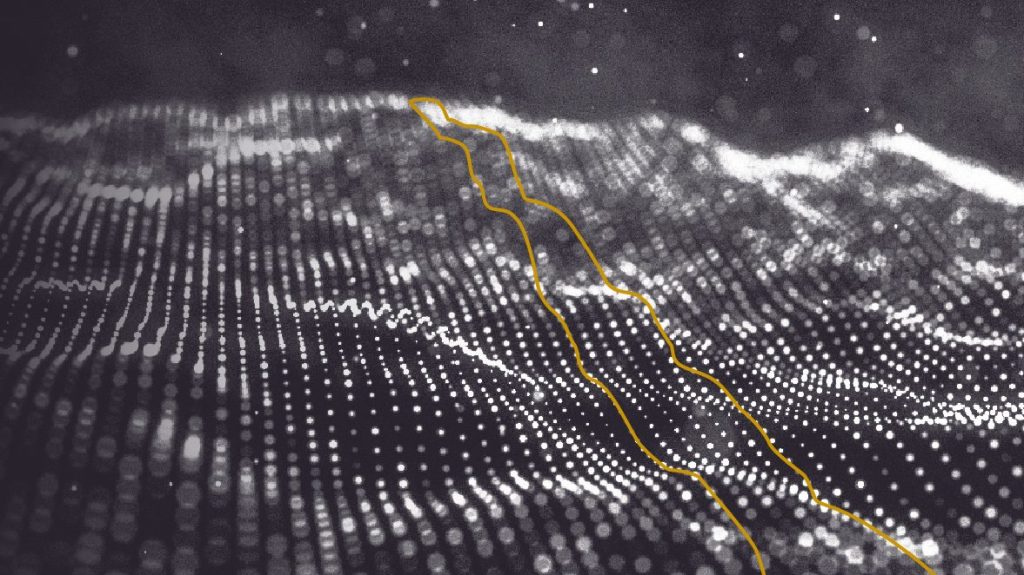

There are two components to the process: first, a visual AI (or computer vision model) trained on thousands of histology images from cancer patients. These thin slices of affected tissue are increasingly being scanned and inspected by experts, though the process can be somewhat approximate.

“This super-high-resolution image tells you a lot about what’s happening at the cellular level of a tumor,” explained CTO Viswesh Krishna. “We run our models on this image to extract a very large amount of features, similar to a genomic panel; we generate thousands of histological reads [i.e. important image features], and take the most important ones that pathologists may be looking at, but can’t really quantify. They might see that they’re different but can’t measure the differences between them.”

Joshi was careful to add they are not trying to replace the pathologist, but augment them. You might think of it as a smart microscope that helps an expert make exact measurements in things like cellular damage, immune response and other structures indicative of how the disease is progressing or being inhibited.

“In the end, the doctor is always in the driver’s seat. This is just more data, and they like it. And bringing tests like this is a grounding external perspective, and patients really like that,” Joshi said.

The imaging component, the team noted, was trained on tons of data and is generalizable across many domains and cancers; counting lymphocytes in breast cancer tissue is largely the same task as doing it in skin cancer tissue. But what that count, or any of the other quantifiable biomarkers the model can identify, says about the patient’s likelihood to respond to treatment is much more limited to specific conditions.

Accordingly, the second component of Valar’s system is what really needs to be dialed in on a particular clinical situation. And to that end, the company has demonstrated that, in the specific case of bladder cancer and the standard treatment regimen, its test is far more accurate a predictor of success than any other metric out there.

Risk factors like age, health history, whether one smokes and so on are variably predictive of certain treatment outcomes, but these are “very crude,” Joshi noted. Valar claims that their AI models “outperform all those variables [in predictive power], and are independent of them” — meaning they can be used in addition to the standard risk factor, not just in place of them.

They also noted that it has been important to keep the results interpretable: The last thing doctors or patients need is a black box. So if it says a patient will respond well, that is supported by “because their immune system is doing A and their nuclei are doing B, etc.”

The company, which was founded in 2021, has spent much of its effort building out the image model and its first clinical model, for the aforementioned BCG therapy in bladder cancer patients. As Valar noted in a recent announcement, the test identifies individuals with triple the normal risk of not responding to BCG, meaning (at the care team’s discretion) it is likely a better move to try something else. If that saves even one month of wasted effort, it could be life-changing for some.

As anyone who’s lived through cancer care can tell you, not only is every day of treatment incredibly valuable, but confidence is hard to come by. Valar may not offer certainty (near impossible in oncology), but it could be a powerful arrow in caregivers’ quivers.

Coinciding with the impending release of its first product, Valar has closed a $22 million Series A round led by DCVC and Andreessen Horowitz, with Pear VC participating.

“The fundraise was perfectly timed,” Joshi said. “We were able to complete this validation, and now this funding will help fuel the commercialization of Vesta, and at the same time we’re starting to expand to other cancer types.”

The founders said they hope to steadily expand, using a commercial lab model much like genomic testing has followed in recent years, COO Damir Vrabac said: “It’s very similar to these other tests that came before us, it doesn’t add any friction to the health system.” That will hopefully allow them to put the cost on insurance providers, and ultimately lower the cost of care altogether by avoiding unnecessary and ineffective treatments.

Comment