When a startup graduates and becomes a “real” company, with hundreds of employees and the first inklings of large amounts of revenue, you could argue that a Team Slide is less important.

Yes, the top leadership team still has to be good, but if the company is growing rapidly, getting new customers and delivering a good product, it’s kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy: If the team is able to grow the company, at least they aren’t completely helpless. But in the early stages of a company, things are a little different, and that’s where a good story around a company’s team is crucial.

And yet, I am surprised how often startup teams are wasting the opportunity of telling the story about their team.

Spoiler alert: For early-stage companies, investors are looking for exactly three things:

- Is there demand in the market? In other words: Is there a real problem here that people are willing to pay to solve?

- Is the market big and growing? Not to put too fine a point on it, but is it possible to build a billion-dollar company in this space?

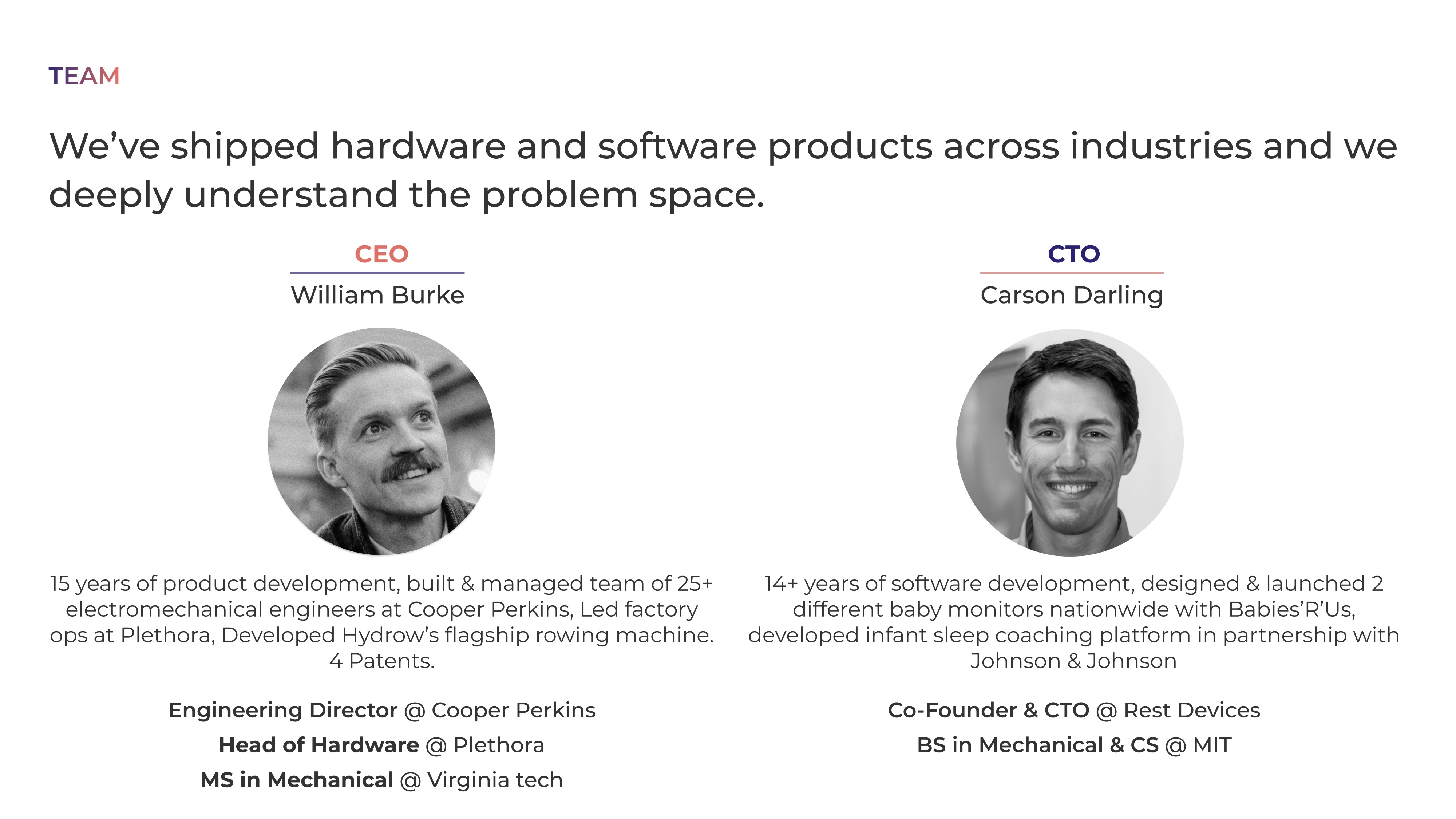

- Is this the right team to deliver? Assuming that the answers to the first two questions are in the affirmative, the investor has convinced themselves that there is space in the market for a big company and that there’s money to be made here. The hardest question is the third one: Do we have faith that this is the right team to bet on?

The ugly truth is that if you have a good idea, chances are that there are 10 other teams working on the same idea. It’s unlikely that you are special enough to have a 100% unique idea. It’s unlikely that you are the first founders to pitch a particular idea to a group of investors. So the question morphs into this: Why should the investors back you and your team?

That is the question a Team Slide has to answer. In this post, I’ll show you how.

How are you special?

What is special about you and your team? Why can’t others easily do what you do? This can show up in many different ways, and it’s your job to show that off. The advantage can come in many different shapes, and of course, every team is different. It’s worth thinking about how your team is special or how it has an “outsize advantage” over any other team that is trying to solve this problem in this space.

Here are a few different advantages that often come up — and ways that they can actually prove to be traps, so be careful!

I should also point out that this article talks about “slides,” but in addition to the things that go in the actual slide deck, there will be a voice-over track where you can pepper in a huge amount of information. I encourage you to design your slides in a way that highlights why your experience is an unfair advantage rather than just lazily sticking a Tesla and a Stanford logo underneath your name.

Technical advantage

For some companies, the founder(s) are literally the only people in the world who have deep expertise in a particular field. This most commonly shows up when someone finishes their Ph.D. research after spending a decade deep in the weeds at the bleeding edge of a particularly skinny branch of the Technology Tree of Knowledge or if someone has been part of developing a new technology or a new field of science.

Be very careful here, though — the knowledge does have to be unique to be a genuine competitive advantage. In other words: If you have a degree in something obscure, but there were 120 other students in your class and everything you learned can be learned from books, that does give you a slight edge. But, the info you have can be “bought” by simply hiring the professor for your class. Unless you are that professor and you have deep and broad knowledge that nobody else has, academia can be a double-edged sword.

A technology advantage also doesn’t mean to have been an engineer at Facebook or Google. In general, there’s a downside to having been at very large companies because they tend to have teams to take care of certain aspects of the business.

If you are a great AI engineer, that doesn’t make you a great front-end engineer, site reliability engineer or security expert. In my experience, people who’ve had long stints at large corporations get good at their little slice of the tech stack but quickly fall out of sync with the cutting edge of other technologies.

In other words: Be very aware of your blind spots and know that while other employers might be impressed by a four-year stint at Facebook followed by a four-year stint at Apple, investors may want to dig deeper into your knowledge before they’ll be fully impressed.

The advantage of deep domain knowledge

Domain knowledge speaks to the “founder-market fit” thing I mentioned earlier. Put simply, it’s much harder to deeply learn a domain than to learn the peripheral skills needed to start and run a company.

If you’ve spent 15 years in the pharma industry and you deeply grok the pain points that the industry is struggling with, you’re probably a more believable founder if you’re trying to solve a problem in that space than if you’re saying, “I’m done with pharma and I’m going to start a mobile games company.”

The way to think of this is that there’s no shortage of folks who give up their well-paying jobs at other startups. They think, “Hey, I can code,” and, “I know how to run a company,” and, “This is definitely a problem worth solving in a market that’s growing.” Even though all of those things might be true, that doesn’t mean that you are the right person to solve that problem.

The perfect founder, in a way, is someone who has shown an enduring passion with deep domain expertise. I know one founder, for example, who lost a child 15 years ago to a particular illness, and the illness was made far worse due to the lack of availability of 3D printing for specific casts. He swears he will dedicate the rest of his life to solving this problem, and I believe him. Using his personal story means that he both has an intrinsic motivation for continuing the work and an almost inhuman stubbornness to solve this slice of the medical industry.

Another example is a startup I know that created a specific tool for teaching surgeons to perform certain surgeries. The founders were both surgeons, which is pretty rare. Surgeons are already highly respected and well paid, and getting one — much less two — to walk away from lucrative careers to build a startup happens very rarely. Of course, this was also an advantage. The medical equipment companies that were the customers for this product know their side of the puzzle but having solved the problem surgeons are experiencing through the lens of actual surgeons? Yeah, that looks very good indeed on a pitch deck.

My first company was a photography hardware company that died a fiery death due to my own incompetence and some bad luck. When I started the company, I had no idea how to run a company, and my coding skills were pretty limited.

What I did have, however, was a lot of deep domain knowledge. As a photography writer, I had written a stack of books about photography, and I’d ghostwritten a few as well. I ran a free photography school and a successful photography blog — all of which meant that when I launched a Kickstarter campaign to try to fund the first version of the product, I could rely on my network to make the first few hundred sales and word of mouth for the rest. That’s a competitive advantage that worked well enough to give the company its fledgling start — without it, it would have been impossible to get it off the ground.

Remember that you might have found a really good problem that’s worth solving, but the next person knocking on the VC’s door might have discovered the same problem and have 20 years of experience in that industry.

Can your team still outcompete the team with extensive experience? If yes, see if you can design a team slide that explains why and how.

“Little Black Book” advantage

Occasionally, you speak with founders who are so well connected in an industry that they essentially know all the major players. They’ve worked together, been to conferences together and argued over the finer details of how to solve certain issues. It’s reassuring to see companies that fall into this category because they have a few important advantages.

They can get angel investors and advisers and hire key personnel from their own industry, people who have incredible depth and context for what is happening in the market and across the industry. That’s a real competitive advantage, and you can weave that into your story and your deck.

Of course, there’s a shadow side to this too; people who’ve been too entrenched in an industry may have their own blind spots as to why certain things are done the way they are done and why there hasn’t been innovation. You need to ensure having a really solid story here. You will want to be able to say something like, “Yes, was building yachts for 15 years, and I know most of the other boutique yacht builders in the world. Here’s how I am different from them, and here is why they cannot do what I’m about to do.”

Startup experience

Being a serial entrepreneur can be a plus or a minus in the eyes of investors. It is true that founders who have made buckets of money for investors in the past have a real advantage. If you had a huge, successful exit, chances are that investors will answer your call when you go looking for money. It means that you’ve seen the lifecycle of a startup, you’ve made hard decisions, and you’ve managed to ride out the wild and tumultuous storm that is a startup once before. The thinking goes that if you survive once, you’re more likely to survive again.

That is true up to a point because all of the other points above still have to be true. Even if you are a very experienced entrepreneur with several successful exits under your belt, you need to answer the question of why you’re the right person to do this specific startup. A good founder with a terrible founder-market fit is going to struggle to raise money unless they’re able to tell a good story about why they are doing this.

One place where I often see this happen is when someone becomes a parent. It turns out that being a parent to a young human is fantastically inefficient in lots of different ways, and an entrepreneurial person can probably come up with 20 to 30 business ideas in the first three to four years of adding to their family.

The problem is that this journey isn’t all that rare. Lots of people become parents, and some of those people are experienced, successful entrepreneurs. I know quite a few investors who are pretty jaded by parenting startups for that reason: By the time the founders have spun up a company and solved the problem, their children are most of the way to being grown up, and the problem that felt so deeply acute at the time no longer feels that urgent or important. Staying motivated becomes hard, and the company finds itself with listless leadership.

Seeing a founder without specific deep domain knowledge doesn’t necessarily equal a red flag but certainly an amber one. Does a new parent really have the depth of domain knowledge that a career pediatrician has? The answer is probably no, so be aware that your potential competitors may be coming at the same problem with greater and deeper experience and understanding of the problem space than you do. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible for you to start a company in this space, but you do need to work hard to explain why you have the X factor to make this company successful.

Substitute “parenting” for any phase of life you can imagine or other fleeting hobbies or interests that founders might have — investors have seen it all, and a founder who bounces from market to market and idea to idea is very high risk. You might be 100% convinced that the current idea is the one, but you’ll have to find a way to convince your would-be investors of that.

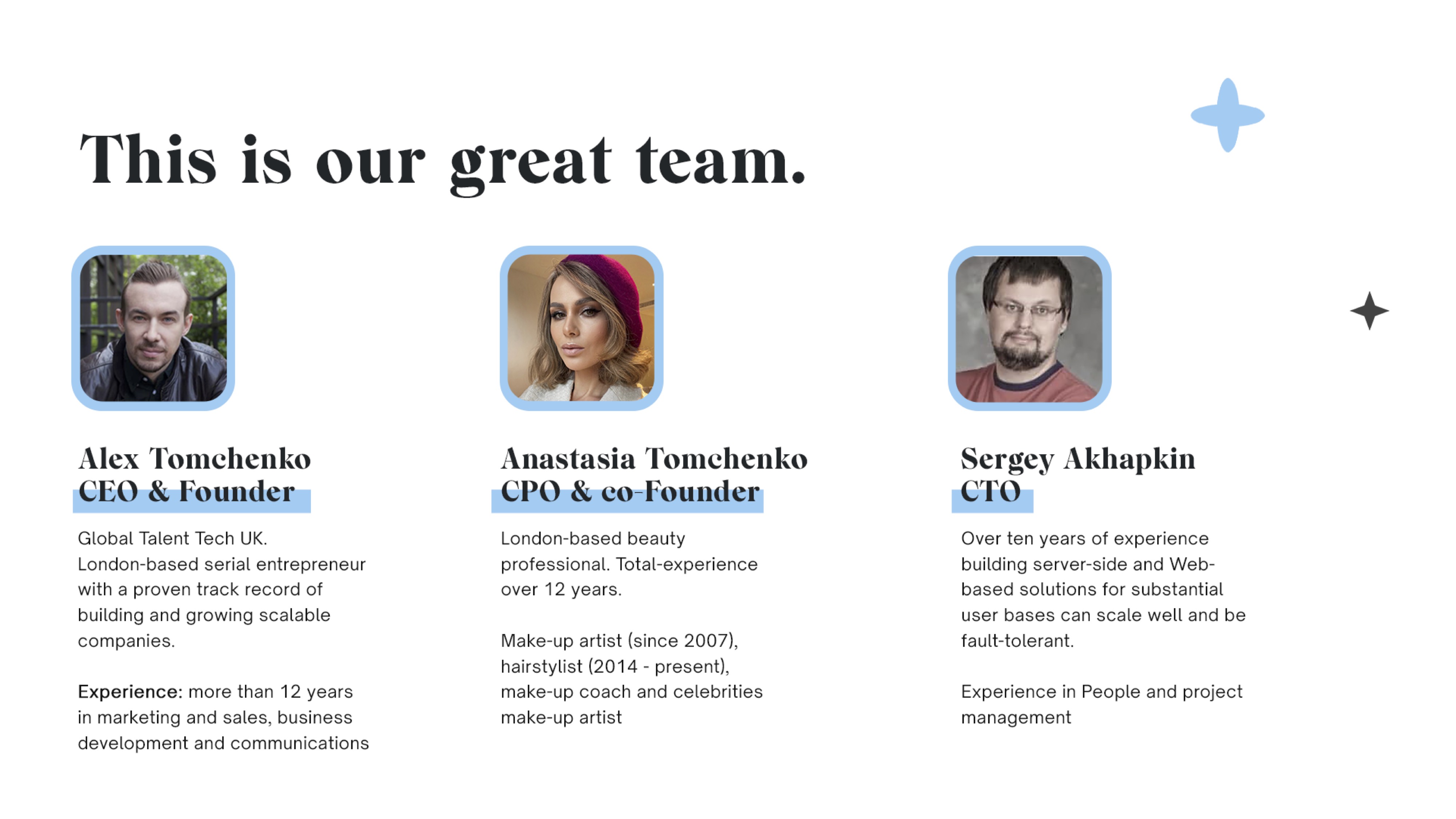

What if I have no “special sauce” at all?

In my consulting business, I sometimes talk to founders who lack the special sauce altogether. They don’t have deep technical or domain expertise. They don’t have a network or a particularly good Rolodex for the industry they are in. They lack startup experience. They don’t have an edge that they can point to.

These are the top 3 most important slides in your pitch deck

Those are typically very hard conversations but in my experience, nine times out of 10, people fitting that profile simply shouldn’t be founding startups. If you can’t hand-on-heart say, “I am one of the best people in the world to be building this specific company, solving this problem in this market,” you are probably in the wrong business. Don’t start a company. You’ll struggle to raise money because for every 10 of you, there will be one founder who does have a near-perfect founder-market fit and will be able to take a route through the startup journey that is just not available to you.

But I also know that reading this article isn’t going to talk you out of starting a startup, so here’s my $0.02: Surround yourself with the smartest, best people you can find, and good luck. Come tell me how I was horribly wrong after your company exited for a billion dollars, and we’ll laugh about it together. Beers are on you.

Comment